Insights from the Cannon Network

Video Transcript

John Newtson: All right. So, I’d like to get started real quick. We have our next presentation is going to be a conversation is with Dr. Indranil Ghosh, he’s the founder of Tiger Hill Capital.

His book, Powering Prosperity is winning international book awards all over the place.

He has, as everyone knows now, who’s listened to me he has a phenomenal CV going back to being an MIT trained scientist. Veteran of both McKinsey and Bridgewater. He was the head of strategy at Mubadala, the 240 plus billion-dollar sovereign wealth fund out of Abu Dhabi. Enormous amount of expertise in private markets, ESG, impact and sustainability and a phenomenal, thinker about the space on a global level down drilling down into actual practical investment decisions.

And we’re going to have Don Yocham. Very famous newsletter editor in the space. Who’s joining us here today.

Don Yocham: All right. So, I’ve heard about. Perhaps. So, this will be a very hot seat extemporaneous conversation. So, yeah, so, so why don’t we just start talking, I’ll ask you the big question that I have when I think about the ESG space. Right? So, on the one level, right.

I, you know, there’s, there’s a lot of mandates around, so I, to me, that opera opens up incentives for greenwashing and stuff like that. So, you have that a level of it too, right? But on the other side, you’ve got actual, efficiencies through, you know, whether it’s solar power generation, which is now cheaper than natural gas, other kinds of renewable and sustainable policies, which actually improve the bottom line in a very legitimate way.

How do you kind of look at that? Right? What’s your economics, what kind of economics are you looking. other than, you know, softer, you know, mandated, things like, well, you know, whether it’s, inclusivity, or those sorts of things, or, you know, whoever else has a stake in whatever stakeholders there are… that doesn’t drive up the stock price sustainably.

Right? It’s the economics. How are you, how do you, how do you balance that and how do you see through that to get apart from what, what actually drives economics?

Indranil Ghosh: That’s a very good question to start with and let me start by actually stepping even one step further back and asking the question. Why does sustainable investment or sustainable investing exist in the first place?

Why is it a phenomenon and what’s it trying to achieve? And what is it? So again, going back to 2015, when the UN introduced the 17 sustainable development goals this was a declaration of a series of initiatives that need to happen for the planet to be on a more sustainable trajectory, particularly in two areas.

One is environmental sustainability and averting climate crisis. And the second one is social inclusion, which is bringing up the living standards of, the poorer economies developing countries, but also the poorer and underserved communities that we have in developed markets like the U S and where I live.

So, these are really existential goals of sustainable development. The challenge that we face now when the UN went on to quantify or try to estimate how much investment it would take to achieve these goals and the analysis that they conducted led to a figure of five to $7 trillion per year for at least a decade, probably much more now, just to put that into context, the global GDP is $80 trillion.

So that means that the global tax. It’s somewhere around $20 trillion. So, if you were to try to fund that five to 7 trillion per year, just from raising taxes, you’d have to raise taxes by about 25 to 30% across the board and even higher in emerging markets because they tend to have lower tax collection, because it’s just harder to do that with the infrastructure that they have.

So, since we have, you know, political meltdown, if we tried to raise taxes by 1%, 25 to 30 is just not going to. So, it’s not the public sector that’s going to achieve this. They certainly have a role to play the, tax dollars that are raised, could be redirected, and use more effectively to pursue some of these goals.

And they are, and any of the legislations we’re seeing around the world, but it’s not going to be enough. Clearly the second level you have of course, is corporate investment, which is. And so that is corporate profits being plowed into, for example, in the case of an oil company, instead of drilling more oil Wells, building, wind farms and solar farms, it was becoming a renewable energy company.

Right. But even that won’t cut it. So, you’d still be left with about two or $3 trillion of investment gap to plug globally. So, where’s that going to come from where it’s going to come from it stores of wealth, both public and private. And shifting those, that wealth into investments that can pursue advanced the sustainable development goals.

That’s why sustainable investing is actually mission critical phenomenon, right. A trend that has to have the impact that we wanted to have. So, let’s talk about where we are in that in that journey. Just like to show you a slide. If this clicker would work, Ah, there you go.

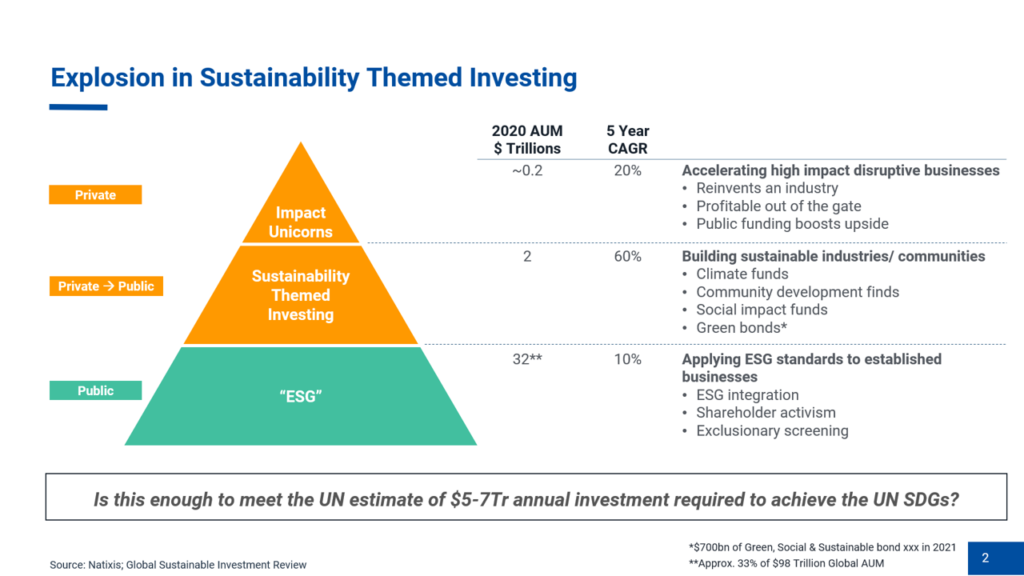

So, I looked at some data from the global sustainable investment review and this puts into numbers the amount of money that’s currently in ESG and sustainable. And, you know, you can see that there seems to be a rather impressive figure at the bottom. There are 35 or $32 trillion that has been deployed in ESG investing today.

But what is that really? So at least half of that is just exclusionary investing. So, investing into funds and other vehicles, which, supposedly don’t have any exposure to tobacco guns, and increasingly to hide. So that may help a little bit by tilting the cost of capital of these sectors to be higher and helping them to, you know yeah.

Persuading them to, to change the other activities in the middle though, you see a bucket which is called sustainability themed investing, and that has 2 trillion, invested in it already. But the interesting thing is that’s growing at 60%. It’s an explosive growth. Now this is in sematic funds like climate funds, social impact funds, and other things, which are again, mainly in listed companies, but increasingly in private markets, but usually larger scale, larger cap, investment opportunities.

Right. But then at the top you see that there’s another bucket, which I’m calling impact unit. Getting to your question, which is only about 0.2 trillion, 200 billion, and it’s only going at 20%. Now this is the capital that would go into companies that are not just cleaning up the way they do business currently, or investing in large scale businesses, which, you know, like renewable energy could have an impact.

This is capital that would be going into truly disruptive businesses that are changing the way business has done or technologically an industry operates and in a way that could have very big direct impact. So, these are game changers now fond that I’m starting, in Q1 of next year, which is on sustainable infrastructure falls in that middle category, the really fast growing one.

So, we’re going to be investing in energy storage, clean fuels. clean mobility, all sorts of large infrastructure projects, deploying hundreds of millions of dollars of capital per transaction. Right. But if our sector is growing at 60% and is it 2 trillion globally, but it’s being fed by an engine which where there’s only 200 billion and only growing at 20% that shows you immediately that there’s a big bottleneck in.

Right to really get the disruptive technologies, which just changed the economics of an industry and make it wildly more profitable inherently they’re profitable from day one and have a big impact. If we’re going to have to push those companies through the funnel, you need a lot more in capital allocation at the top of this pyramid.

And this is where I think the opportunity is for the financial publishing industry. Because by mobilizing individual retail capital and the sort of access that you have to self-directed investors into the top of that pyramid, that is the way to unlock. The entire sort of sustainability, that’s the sustainable investing bottleneck.

Don Yocham: And that bottleneck exists, because you know, most, to just, I’m going to make a statement, you tell me right or wrong or correct me.

I mean, VCs continue to move up and up and up as far as what their minimum investment is. I mean, you got 50 million, a hundred million dollars now is kind of the threshold for a lot of them look at, so they just can’t even. I mean, they have to do a hundred to 200 of these different investments, which is just way too much for them to manage.

So, so that’s, that’s where it, any kind of on the Reg A phenomenon, you know, reg CF and along with all of these other, whether they, how they raised the money, but this, this kind of middle tier of companies that need five, 10, $20 million. Right. And they just can’t get the attention from the big guy.

They just, just need that exposure. Right? So that’s a gap. So, there’s this massive gap. That’s just pulling that, creating this vacuum. And that’s an opportunity, right?

Indranil Ghosh: That’s exactly right so when you look at the venture capital industry, first problem is that the ticket size, the average ticket size is getting higher and higher.

Because capital tends to get concentrated into the most, most successful GPS.

Don Yocham: Oh. And they had, they also only have so much attention right now, and there’s only so many things.

Indranil Ghosh: And so, it just, there’s just, just the minim size that they can work with on top of that, that tends to be a concentration in certain sectors.

Right. So, it’s technology, it’s crypto biotech is a few things, but not enough towards the kind of a much more capital-intensive. Hardware intensive manufacturing, intensive companies that we need to promote. If we’re going to clean up exact as like energy sectors, like agriculture transport for this type of stuff, you don’t just write stuff software, you have to build stuff.

Don Yocham: So that’s the characteristic of this, this sector is, is very capital-intensive industries for the most part.

Is that right? Yeah. And so often the cycle that you see for one of these companies is that. You know, one, two, 3 million to develop some technology, then it needs, you know, maybe another 5 million, 10 million to, to develop a pro a five million to, to do a pilot plant or a pilot project of small scale of infrastructure to show that thing works, but it needs another 10, 15 to develop its first project.

So, work with customers to get long-term purchasing contracts for energy or whatever they’re producing to get the land and the permitting to build. So, it’s quite a long and expensive process. So that set of activities is usually the bit that’s quite under underfunded, but when you get to the stage of having the first factory ready to, to build, and as, as that chart is showing lots of funds that growing at a very rapid rate, ready to fund that first project when the hard work is done.

So, from my perspective, you know, in order to have good deal flow and not be fighting with all my competitor, I need to make sure that the top of the pyramid is really well-nourished

right? Yeah. Yeah, no, that’s great. So, give me a couple of instances. So, like in Iceland, right. They just launched a carbon capture plant.

Right. I’m very curious about that kind of stuff. Certainly, small scale has no idea how much capital went in to actually build that. Right. But if you, if you, of the things that you’re seeing, as far as these potential impact unicorns, What’s the one in like one or two things that just feel most exciting or most, most impactful?

Well, from an investor standpoint and actually in achieving goals.

Indranil Ghosh: Well, a couple that I really like are agriculture related topics like vertical farming or regenerative agriculture the area of clean fuels I think is really interesting. So similar to what you’re talking about with this project.

There’s another series of companies out there. What they’re doing is they’re taking renewable energy from wind solar, maybe hydro energy and using it to electrolyze water, to split water into hydrogen and. oxygen. and then they’d take that clean hydrogen. And that could actually be used as a fuel directly in certain situations or industrial feedstock.

But what you can also do is through a relatively inexpensive chemical reaction, combine it with carbon dioxide. That’s given off by some industrial process, say it’s a brewery or a refinery should otherwise go into the atmosphere. So, you do the chemical reaction, and you get back to a fuel like kerosene.

Or, you know, methanol and given that aviation and shipping and heavy-duty road transport are some of the biggest carbon emitters. If you can take carbon dioxide that would have otherwise gone into the atmosphere, make it back into a fuel with clean hydrogen, then you’ve gone a long way to clean up the mobility sector but in a way in which it doesn’t require too much changing of the actual planes and ships, because are still using the same field that you were before, it just made more cleanly.

Don Yocham: Right. So, what is it in your view then going to be? Liquid fuels with much higher energy densities, although you lose a lot of efficiency and conversion, right.

And combustion engines are maybe 25% efficient if you’re lucky. Right. So, is it that process and maintaining the liquid fuel infrastructure, you know, whether it can be ammonia, hydrate from hydrogen, you know, or anything like that, other fuels like you talked about, or is it lithium -tech lithium -ion batteries?

I mean, which w you know, they, if they, if they work on the energy density problem, if they can break through that over the next five years, you know, then it kind of becomes on par, how do you, how do you, what do you think is how it’s going to break that way? Or are there maybe you can cop out and say, it’s going to be some of both

Indranil Ghosh: I’m going to say that the, that the market and the innovation of the industry decide ’cause, I don’t think we need to make that call. Right.

Don Yocham: And it’s, and it’s too hard to tell, right?

Indranil Ghosh: We simply don’t need to make that call because there’s going to be certain parts of transportation, which are just very hard to do with hydrogen or with a battery. The battery is too heavy.

The hydrogen doesn’t have any enough energy density. So, if, until the technology is there to power a plane with a battery with enough energy density and not lighten up. Well, you know, what can we do what we can go with clean kerosene? So basically, not changing anything about the way that the plan operates is kerosene is cleaner.

Now, if it could be run on a battery, which is fully powered by renewable energy, well, that would be fantastic, but maybe we need 10, 20 years for that. Yeah.

So, we need transition technologies just as much as we need, you know, an end state solution that is complete. Carbon negative maybe, not carbon neutral.

Don Yocham: Right. Great.

Well, I appreciate that answer. Have you got more of this? I didn’t get prepped in advance.

Indranil Ghosh: Well, we didn’t have to look too much at the slides, but I think one of the things that’s probably worth talking about is, you know, if sustainable investing is going to work and if we are going to actually have the kind of societal change that we need to be more sustainable.

A lot of stuff is going to change. The whole system needs to change. So sustainable investing is predicated on a broader system change. Otherwise, it’s not going to work. Yeah. So, is that going to happen? I would say that’s almost a fundamental question. We have to answer.

Don Yocham: So, another aspect of that.

Okay. So, you’ve got this from the technology on the climate side. Right. And so that’s a clearer payoff, right? Then you’ve got the social side and you mentioned you referred to it earlier and it’s actually something. Pretty intriguing to me is, is how do you unlock that capital?

The native capital that you know are in underdeveloped countries, but that capital isn’t liquid right now. Right. And to my way of thinking so much of that has to do around property rights. Sometimes in some countries that’s, well-defined in some countries it’s poorly defined.

What do you see happening as past to, if more clearly defining those property rights and then the mechanisms that they have in order to make that liquid, allow them to monetize it?

Indranil Ghosh: Property rights as a fundamental issue, as well as just general business friendliness practices, like being able to get your money in and out of a country, easily having a well administered tax regime and so on, and being able to get permits, being able to start a company quickly.

So, there’s a lot that can be done in all countries, but particularly emerging markets where these capabilities aren’t there yet to sort of make those, those, legislations more business friendly. But I think the next step, you know, once that basic framework has in place, and maybe this is where we’ll use one or two more slides.

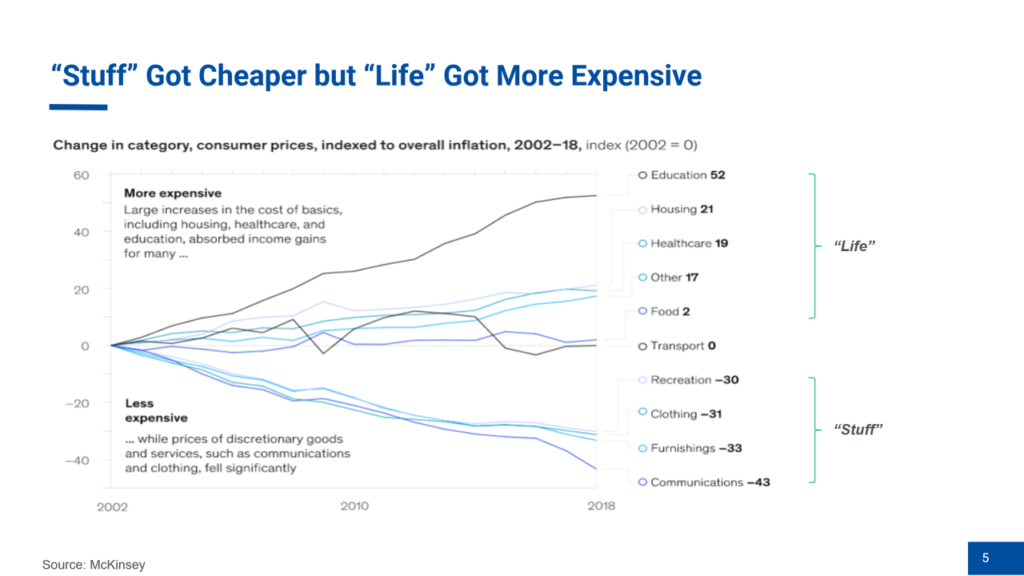

Talk about what else is necessary. Now, this is a chart that is, I find very interesting because this actually, although mostly focused on developed markets is even more true of emerging markets, particularly in large cities, in emerging markets, where what you see here is the real cost of different things and how they’ve evolved over the last 20 years what this chart shows is that some very basic things like healthcare, education, housing, , you know, transportation they’ve gotten in real terms much, much more expensive and that’s even true in places like Mumbai and Shanghai, you’ve had massive concentration of people in a short time into cities.

Right. But at the same time, electronic. Cars clothing it’s got cheaper. So, the way I say this is stuff got cheaper, but life got a lot more expensive. Now, the more that life gets expensive, it means that people are locked out. They don’t get access to developing their own h and capital. They’re not healthy.

They don’t get better educations. They haven’t under savings. Have a poor housing. It’s very difficult to become the best version of yourself and be productive as you could be, which is a very big shame economically. Right. And actually comes back to haunt economies and actually ends up hurting things like the birth rate.

This is probably one of the contributions to falling birth rate is this lack of access. Right? Right. So, one of the things that’s really important to fix on the social inclusion side is to improve access to all. Life factors, these basic factors. And that’s where I think we can use not just technology, but improvements in zoning laws, and community investment, laws around enabling regions to be more in control of their finances, to invest in things that are most suitable for them to become competitive the global economy.

By investing more into these more basic, more fundamental things about life and these sort of social services, absolutely critical to upgrading capital, which is ultimately the driver of all productivity. Because with that, you get more innovation, more wealth creation, and more investment into further sustainable development.

Don Yocham: Where does that fall? Is that more governance or is it more structure or less? What’s your view?

Indranil Ghosh: It’s got to be a bit of both. That’s where it’s not a cop-out, but that is a partnership. Yeah. Okay. So, you’ve got to think about what the role of the public sector is and what’s the role of the, of the private sector.

Now, at least in my view, the private sector is really good at making short-term investments into lower risk. A bet on type of commercial activities, right. And it’s very good at allocating resources to make these short-term resource investment decisions, whereas not so good is taking a very long-term view.

We’re talking about decade long of multi-decade view, which is what we need to take when it comes to sustainable development. It’s not necessarily good at taking very early-stage risk as that pyramid showed.

It’s not good at investing in basic science or even translational science, for example. And so there’s a role for the public sector to take on some of those responsibilities by incentivizing innovation, not picking winners, providing more incentives for technologies and businesses to flourish all these different areas, so no need for the public sector to choose whether it’s going to be batteries or clean fields, just support them all as the department of energy is doing with its loan program right now, for example, so incubation, you know, smart incubation, but without picking winners, there’s an important role for the public sector in having a longer term view, being able to provide longer term capital, which will help some of these companies that we saw at the top of the pyramid bridge through over several years of development to being ready for private funding, these are the kinds of roles that the public sector in play.

Don Yocham: So all at the back to the top of that pyramid on that, on that unicorn side, I mean, how many, how many you know, different companies are in a, you know, in some, you know, do you see in a viable position that would warrant investment because is it hundreds of thousands. I mean, you know, if you look at the numbers get pretty small sometimes for the companies that I, as I look across it, but that’s usually just in the U.S. so like how wide open is that field as far as people in different initiatives?

I mean, is it thousands?

Indranil Ghosh: Well, what I’m saying is there’s thousands of companies. Yeah. There’s actually a huge blossoming of innovation in both the zero carbon, as well as the social inclusion companies and frankly, this starved the capital at the top of that pyramid. I’ll just show you again, another slide, which is, this is just some of the deals that I’m working on.

So, one guy and his team. Okay. All sorts of deals across all of those themes, which a lot of them had to do with, you know, green, green, energy and industrials, clean transportation, food, water, and waste. Also, a bit of social inclusion. Now the numbers in red are the amount of capital that’s required to get through that early stage, just to develop the technology, build the first pilot plant, you know, put in place a project, develop a project that could then be a full-scale commercial plan, but needs the next round of funding.

The numbers in black are that next round of funding. Okay. So, you can see that just on this page, what I’ve curated is multi-billion-dollar pipeline, right?

Right. The right-hand side is what funds like mine can do later on. This is about $ 4 billion on the right-hand side in black on the left is about $500 million.

Yeah. That is a funding gap because very few of those companies have yet found VC. Some of them have, and eventually they will.

Don Yocham: Are they are many of them just still on paper then.

I mean, if they, you know, I could, if funding is scarce

Indranil Ghosh: They’ve, you know, they’ve gone to their friends and family. They’ve done a few family of babies and minim viable product in operation. Okay. Right. But to make it to the stage where they got that first commercial scale project, they need a proper slug of capital.

Yeah. And many of them will get that VC funding or funding from friends and family. It’s painfully slow.

It’s going to take a year or two years. And this is where, by mobilizing the financial publishing industry, being able to get self-directed investors into these types of deals at scale, at high velocity, we’re going to unblock this sustainable investing problem and actually accelerate all the things that we need to do to decarbonize the planet.

And, you know, have worked so we have somewhere livable, you know, 20, 30 years from now.

Audience Question: Thank you, on the slide about, life getting more expensive. Healthcare is one of the things that got more expensive. And I think, personally even doing pretty well by societal standards, I know that healthcare costs are a non-negligible source of stress in my household. And if it’s a stressor for us, then, you know, I, I think the average person in society is hurting even more.

This is also true in China. I lived in China for 10 years and even people who were in the upper half, the society in China have this concern around healthcare. It seems to be a kind of global problem. I also notice it’s missing from the pipeline slide. And so, I’m curious how does sustainable investing and, or the kind of just general, elevating of standards that everything you’re talking about represents with regards to investing hit healthcare.

What are some examples, that, that might look like they don’t have to be tangible, but just like, what does it look like? How do we think about all of this stuff as it intersects with healthcare?

Indranil Ghosh: Again, I think, with healthcare. We’ve got to focus on the services, which if you provided really well and relatively in a low-cost way, but a high enough quality way would address 80 to 90% of all healthcare issues.

And those are things like vaccination, preventative health. It’s actually things like encouraging, sports and wellbeing very early in the education system so you set, good habits. It’s a very good, you know, initiative in Iceland coming back to Iceland few years ago they found that all the young people, because there was nothing to do in the cold winter evenings, we’re just going out drinking.

So, it was becoming a sort of a drinking problem, which is obviously having a health impact. And also, just general productivity impact on the economy. So, what they did is they really tried to start it to promote sports and wellbeing in the schools and they found, and the, in the provided recreational facilities, right.

For people to go and play a sport indoors during the long-haul winters and lo and behold drinking rates fell health, improved educational attainments. Right. So healthcare isn’t always just about literally hospitals and medical technology. It’s actually impacting the whole lifestyle and culture of a generation that can have huge health benefits.

Okay. But then of course you actually have to have healthcare, but it turns out that all of the medical procedures that there are the thousands and thousands that there are, there’s only about 20 or 25 that really address that you absolutely need, but you need to provide to everyone to address 80 to 90% of all the sort of surgical issues that are required.

Those are things like childbirth, appendicitis, so common, but you know, simple interventions, but you need to have, you know, clinics everywhere, all around the country, providing that in a low cost, easy to access way. So, making those types of smart investments actually improves healthcare outcomes significantly.

Whereas what we seem to be doing is spending more and more money on drugs and very expensive medical interventions, because we didn’t get the upstream part of it right. Which is can improve good, healthy lifestyle.

Don Yocham: Yeah. You know, and that’s, that’s kind of why you don’t see it on there. Right. It’s healthcare that kind of you’re talking about.

Basically, more doctors and infrastructure are not that investible doctors and the infrastructure absorb most of the costs. Right. And rightfully so. Right. And that’s why the investment is going to drugs because those things have a payoff for the investor. So, it’s really, a social balancing problem of how do you either encourage more hospital? How do you encourage more healthcare? How do you encourage more vaccination rates? Right. And, and this is not, it’s not as directly investible, I think, would be my feeling.

Indranil Ghosh: You know, health care like prisons is an aspect of that, which is really a public sector activity. It needs to be funded appropriately and efficiently through the public sector, but then above a certain threshold, you know, more elective and complex surgeries and therapies, which are inevitably required.

Maybe that’s more of a private sector should but I think there’s a lot more investment in that upstream social health care. Okay, that needs to happen. That’s not to say that healthcare and the there aren’t a lot of great health care companies to be invested in. I wouldn’t say that it’s not investible.

It’s just that if you’re trying to get sustainable outcomes, I think you need to focus a lot more on these health and wellbeing aspects of healthcare.

Audience Question: Now, you had mentioned crypto as a, an investment vehicle in the beginning, but my question would be. With all of the miners, not just with China, but all over the world that are coming to the U S and the energy needs that they’re going to require over the next five to 10 years, you know, multiple gigawatts.

Do you see a lot of sustainable investment going into that industry? Because, I mean, in my opinion, us, at some point is going to require a certain amount of sustainable energy for these companies as they let the, all in. And then they’re going to tax the heck out of them, but

Indranil Ghosh: which companies that are lending, I didn’t quite hear you.

Audience Question: Oh, you’re talking about all the mining companies, all the crypto miners, manufacturers, Bitmain. Kanaan, they’re all here. They’re all coming here now. They’re all there. They’re snatching up all the, all the land and they’re building mining factories and they’re using all different types of energy. So, I mean, that’s the plan for the next five to 10 years.

They want to come to the U S. It would seem that there’s going to be a requirement at some point that a percentage of their mining is going to have to be coming from sustainable energy.

Indranil Ghosh: This is actually a really important point because it’s not just crypto, right. But it’s data centers. The whole digital ecosystem runs on an enormous amount of energy.

And so, you know, when we talk about the energy transition and people think it’s just about wind farms and solar. It’s really not because the energy content of so many industries is incredibly high and digital industries, crypto data centers is, is absolutely in

Audience Interuption: far surpasses as some of the things that are happening now, massive amounts of energy are going to be required.

Indranil Ghosh: 30% of food production is actually energy. So, the reason why vertical farming in my view is that impact unicorn. Is because if you have an indoor controlled environment growing facility, that’s very, very large scale. We’re looking at something in New York, it’s 400,000 square feet of seven football fields.

There’s run on renewable energy and manure digesters. So, it’s, you know, consuming its own renewable energy and has enough left to sell back to the grid. These are very disruptive business models because you transform the economics of food production completely. Traditionally in, in normal agriculture, you have sort of an EBIT margin of 10%, right?

Because you’re paying for the fertilizer, you’re paying for them, you know, the energy in one way or another, right. You’re paying for, you know, a lot of machinery. But if you’re doing that in a much more controlled environment where you’re growing 24/ 7, 365, right in optimal conditions, you can grow fruit, a seasonally so get higher prices because you’re growing it in. And at the same time, your energy bill is almost zero because it’s coming from your solar panels and the, the, the sort of the Agri-waste that you’re producing, you can actually sell it as fertilizers, compost to other farmers.

So, things that used to be costs in normal farming or actually revenue streams, because energy is now a revenue stream.

You’re selling the surplus to the grid. You’re selling your Agri-waste as many, or your EBIT margins go up to 70, 80 percent. So, you’re having a great deal of impact. You’re also able to locate that vertical farm right next to a city and not have to transport the food from Arizona or California. So, the carbon footprint impact is huge.

You’re hugely profitable. But going back to your question, you know, I think, when it comes to digital, these are also very disruptive technologies because they can, you know, have a big bearing on disrupting and making more efficient other industries. But the energy component of it can’t be ignored and it needs to run on renewable sources, which is why we need to continue plowing more investment into all kinds of new, renewable energy.

Don Yocham: They’ll pull on whatever its source of energy is out there. And if it’s more sustainable than then, that helps solve that problem. Then on the CO2 front and so the various different bottom-up type of initiatives that are, you know, tackling them, one of the major contributors is just simply plowing the land in the spring.

Right. I mean, that throws up almost more than I think automobiles. Right. And so, what are, apart from the vertical agriculture, right? Yeah. Is, are there other, initiatives, technologies, just, methods of trying to get people to change their habits? What do you, what do you see as far as a way to impact that?

Indranil Ghosh: there’s a company on that page right there that addresses that problem. Huh? So, it’s a company called NoviHume. It’s a German company. NoviHume over here, what it does is it takes brown coal, which is lignite excavated from a coal mine. And instead of shutting down the coal mine, you continue to dig the coal, which is good for the workers, but now you treat the coal with a proprietary approach, and you create a soil enhancer.

So, you apply this a soil enhancer to, to the fields every year, and you don’t need to apply any fertilizer because what it does is actually improves the soil structure increase, increases the growth of the root structure on the, on the plants and what you end up doing is actually increasing the carbon content of soil after several years of application and increase the nutrient levels and ultimately the nutrient levels in the food that’s grown itself.

So instead of normal agriculture, which you absolutely right, rightly pointed out, leads to carbon being released from the soil cause you plowing it every year is sort of lying. Fallow, blown away. All the carbon dioxide sort of goes into the atmosphere,

Don Yocham: Plus, all the nitrogen, which was produced through carbon intensive processes that goes on the fields to begin. Right top of that,

Indranil Ghosh: Instead of you apply NoviHume and vastly improves the resource structure, sequesters carbon from the atmosphere and gives you higher quality food and the combined with crop rotation and other regenerative agricultural process. Right. You ended up making your soil richer and richer every year.

And this has been proven through 12 years of research, right, right. On field side by side, farm regeneratively and farmed conventionally. And you see the complete, you know, differences in soil structure, carbon content, nutrient levels. Yeah. So is this kind of, technology’s a perfect example. People think we coordinated beforehand, but we didn’t perfect example of the kind of company that’s looking for funding.

It was finding it painfully slow but could be accelerated significantly. So, they are building a factory in Germany and in the U S and you know, help support this regenerative agriculture movement.

Don Yocham: Was there a mechanism for a… John? How are we doing on time? I wrap it up. Okay. All right. I’ll just skip my last question.

I’ll open it up here for one last question from anybody out there.

No. Okay., all right, well then thank you. This has been great conversation. Everybody appreciates your patience with this kind of winging it.

About the speakers

Dr. Indranil Ghosh is a sustainable investor, MIT-trained scientist, author, and strategic advisor to governments and leading global corporations with access to high-quality private market companies currently raising capital.

Prior to Tiger Hill Capital, Indranil was Head of Strategy at Mubadala, Abu Dhabi’s Sovereign Investment and Development Fund, and held senior roles at Bridgewater Associates and McKinsey & Co.

His recent book, Powering Prosperity: A Citizens’s Guide to Shaping the 21st Century, has won multiple international book awards.

Dr. Ghosh has a robust pipeline of sustainable & impact focused private companies raising capital. If you’d like to connect with Indranil to discuss co-investing in his deals please go here to send us a message and a Pendry Cannon director will assist you.

Click on the book image to get your copy of Indranil’s award winning book:

Don Yocham cut his teeth in the bond option pits of the Chicago Board of Trade where he traded commodity and financial futures, options, and stocks for institutional clients. Then spent several years at PIMCO before moving to managing investments for wealthy clients for firms ranging in size from $250 million to $16 billion AUM.

Don publishes investment newsletters at The Prosperity Project, where he focuses on helping individual investors understand and navigate the impacts of centralization vs. de-centralizatoin, exponential technologies, and more.

If you’d like to connect directly with Don please go here to send us a message and a Pendry Cannon director will assist you.

Request a personal introduction: